Ọlábíyì Babalọla Yáì BetweenTime, Space and Eternity

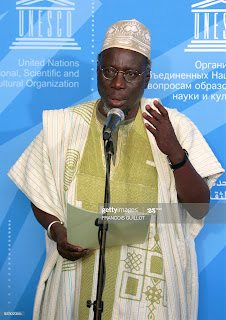

Ọlábíyì Babalọla Yáì giving an address at UNESCO

I opened WhatsApp on my phone on the 5th of December 2020 and read a message from Toyin Falola that Ọlábíyì Babalọla Yáì had passed away.

Falola, who, in his In Praise of Greatness, visualizes himself as a

visitor from the Great Beyond transmitting messages between those on Earth and

those who have gone beyond Earth, broke this news about the luminosity that is

Yai, the light ever shining, burrower into the crevices of the Yorùbá knowledge

cosmos, poetic thinker, whose insights and expressions are like diamonds in

darkness, you left the world of academic scholarship for the broader scope of UNESCO, yet persisting in the continuous flow

of the river of knowledge that you are, you have now left the world of Earth for

that zone mysterious, from which messages come only in dreams and revelations,

leaving us to assemble the constellation of knowing you bequeathed us, even as

we anticipate your inspirations exhaled upon us as rain fertilizing hungry

earth.

Dew pour lightly, pour lightly, dew pour heavily, pour heavily, dew pour heavily, so that you may pour lightly, these were the declarations of Ifa for Origun, when going to coordinate the creation of the vast expanse of the universe during the dawn of time, thus Ifa’s wisdom was consulted for Olofin Otete, who would pour myriads of existence upon the earth.

Our aspirations in relation to your inspiration are akin to those depicted in that collage of translations of the Yorùbá poem, “Ayajo Asuwada,” compiled by myself from Babatunde Lawal’s The Gelede Spectacle, itself building on Akínsolá Akìwowo’s translation in “Contributions to the Sociology of Knowledge from an African Oral Poetry,” and from a rendition of the same poem by a translator unknown to me in a version published in the Universal Ògbóni Philosophy and Spirituality WhatsApp group.

Every system of knowledge needs inspired and inspiring interpreters to project its everlasting beauty and power, its unique force within the configuration of efforts to make meaning of existence.

Amidst the countless words, in essay after essay, book after book, continually

written about the thought and cultures emerging from the Yorùbá of Nigeria, the

words of Ọlábíyì Babalọla Joseph Yáì stand alone.

I am not aware, for example, of any formulation of the conception of essential

identity in the Òrìsà cosmology of the Yorùbá superior to that of Yai.

Even if some others I might later learn about do demonstrate an equal level of pithiness and communicative power all at once, Yai’s will remain forever in my mind as evoking the sense of aspiration after ultimacy that is humanity’s greatest quality, depicted in terms of incantatory memorableness that forever illuminates the landscape of the mind, side by side with other great formulations of ultimate human identity, from Asia to Europe to Africa to the Americas and beyond, answers to the fundamental question by the two legged creature who dominates Earth but who does not know where he comes from into the Earth or where he goes to when he leaves Earth, the question “who are we?” :

Orí is “essence, attribute and quintessence… the uniqueness of persons, animals, and things, their inner eye and ear, their sharpest point and their most alert guide as they navigate through this world and the one beyond”

(Ọlábíyì Yáì, review of Henry John Drewal et al, Yorùbá: Nine Centuries of

African Art and Thought, African

Arts, Vol. 25, No. 1, 1992, 20+22+24+26+29, 22).

The other particularly memorable expression of this idea known to me is “The Importance of Orí,” an extensive ese ifá, a story from the Yorùbá origin Ifá system of knowledge, published online in Martin White and Jack Mapanje's African Oral Poems site and in Wándé Abimbólá’s Sixteen Great Poems of Ifá.

Various deities are questioned about their ability to follow their devotee on a distant journey over the seas, each proclaiming such undying loyalty until he or she is asked a question along the lines of “what of if, as you are travelling and travelling, you come to the town of Orangun, the place of your most fervent worship, and you are offered your favourite delicacy, deliciously glowing yam pounded into a soft, spotlessly white ball, covered with exquisitely flowing soup, rich with beautifully seasoned meat and topped with the purest palm wine, what will you do?”

“I will eat my fill, and singing joyfully, will return home, riding on the majestic acrobatics of crabs, elevated above earth on legs strong and numerous, elegant and swift,’’ each deity replies along such lines, to which the questioner responds, “you are not able to follow your devotee on a distant journey over the seas.”

Having been vanquished in their claims of absolute loyalty to their devotees,

the deities implore of the questioner, “Gbọlájókòó, offspring of tusks that

make the elephant trumpet,’’ holder of titles in cities multitudinous, Òtan to Ẹléjèlú,

Eléré to Ìláwè, sage both sublime and childlike, “we confess our helplessness,

please clothe us with wisdom,’’ my summation adapting the idea of the childlike

from another great summation of this cosmology, Wolé Sóyínká’s seven stanza

poem The Signposts of Existence from his Credo of Being and

Nothingness.

In response, the teacher expounds the concept of Orí which Yai has distilled in those lines that are rich enough in ideational density and expressive power to stand beside the classic ese ifé as mutually illuminating texts within the scriptural universe of Òrìsà cosmology, the congregation of expressions of the inspirational depths of the tradition.

That is the world where Yáì belongs, the world of the gbenugbenu, as he describes it in another magical piece, ''In Praise of Metonymy: The Concepts of 'Tradition' and 'Creativity' in the Transmission of Yorùbá Artistry over Time and Space,'' the world of the scholar as acute thinker and verbal artist.

In his own case, he is the scholar as the confluence of the finest fruits of

ancient cultures, from Africa to Europe, from the classical cognoscenti of his

native Dahomey to the refinements of the

Sorbonne, crucible of the European scholarly tradition as the matrix where

foundations of European civilization were developed at the intersection

of Greco-Roman classicism and Christianity.

His immersion in cultural universes ranges from the matrices represented by his

training by classical African thinkers

to the Paris of the Sorbonne, luminous in

European history as a birthplace of modern Western creativity in the arts, to

Ile-Ife, described by Yai as the university par excellence in Yorùbá

history, where specialists of various disciplines created a ferment of knowledge,

a culture he was immersed in through its modern expression at the intersection

of university and city, to Ibadan, crucible of modern African thought and scholarship.

His

higher academic education and professional development commence from his Licence èt Lettres (Espagnole et Etudes

Latino-Américaines), 1964 and Certificat d’Etudes Superieures de Linguistic

Generale, 1965, at the Sorbonne, the University of Paris.

They continue with Post Graduate Diploma in Linguistics at the University of Ibadan, 1969, and his life as a scholar at the University of

Dahomey, 1971-2, University of Ibadan, 1972-4, Centro de Eastudos

Afro-Orientais, Universite Fderale de Bahia, Bresil, 1975-1976, the then

University of Ife, 1974-1988 and the Centre

of West African Studies, University of Birmingham, 1987.

Those spatio-temporal and civilizational axes are the framework of Yáì’s educational

formation and the zones of his

foundational scholarly creativity, before his move to Kokugakuin University,

Tokyo, 1987, and eventually to the

University of Florida, 1988-1998, progressions

within which he rose from a linguistic assistant to Research Fellow to

Professor in universities on various continents

and Institute Director, along with consultations in many international

capacities, activity in various academic initiatives across the globe and his

eventual full time entry into UNESCO as permanent delegate of Benin.

His work oscillates at the intersection of

the theory, poetics and politics

of African and particularly Fon and Yoruba languages, oral literatures

and religions with African philosophy, in the context of intercultural contact between Africa and its

diaspora in Brazil, Cuba, Trinidad and Tobago and the United States.

Deeply African in culture, he was also an assimilator of Western high culture, the

“only person I know who

can move with utmost ease from Beethoven's symphony to Fọ́yánmu's poetry in

one sentence,” as stated in a Facebook comment by his protégé, Professor Adeleke Adeeko.

Like Noureini Tidjani- Serpos and Ahmadou Hampate Ba, he represents some of the

finest fruits of the Francophone scholarly and artistic intelligentsia who

eventually entered into high level service with UNESCO.

Even in UNESCO, he continued scholarly writing and publishing, as indicated, for, example, by his “Yorùbá Religion and Globalization: Some Reflections,” published while he was in UNESCO.

I suspect, however, that Yáì’s better known publications are not many, in fact perhaps

no more than about four, in my estimation, the best known, as I understand it, being ''In

Praise of Metonymy: The Concepts of 'Tradition' and 'Creativity' in the

Transmission of Yorùbá Artistry over Time and Space'' complemented

by “Tradition and the Yorùbá Artist.”

“The Path is Open: The Legacy of Melville and Frances Herskovits in African Oral Narrative Analysis” is another spectacularly powerful and well-travelled essay, given the various places where it has been published.

His review of Henry John Drewal et al’s Yorùbá: Nine Centuries of African Art and Thought is another scintillating, and, for me, indispensable work on Yorùbá civilization which also has significant visibility, being published in the famous and long lived African Arts journal.

In a personal communication, the master states

that many of his writings are lost, but that of those still accessible, a

collected edition is forthcoming.

We shall thereby be able to read such pieces as “From Vodun to Mawu: Monotheism and History in the Fon Cultural Area,” “Understanding Africa,” “Theory and Practice in African Philosophy: The Poverty of Speculative Philosophy,” “African Diasporan Concepts of the Nation and their Implications in the Modern World,” “Texts of Enslavement: Yorùbá Vocabularies from 18th and 19th Century Brazil,’’ “Intellectual Responsibility and the Responsibility of Intellectuals,’’ “Translatability: A Discussion,” “African Ethnonyms and Toponyms: Reflections for a Decolonization,’’ “Issues in Oral Poetry: Criticism, Teaching and Translation,’’ ''Conjurer le Spectre du Grand Linguicide, Langues-Cultures et Décolonisation des Humanités, '' ''Conjuration of the Spectre of Grand Linguicide: Languages, Culture and Decolonization in the Humanities'' [my translation]

These are among titles more of which may be seen in the latest edition of his CV available online, although it might not be up to date , Yai stating in an email this year that had lost interest in writing CVs for about twenty years.

Sending me a list of his publications on the 4th of September, 2020, about three months ago, he added:

My publications while I was ambassador at UNESCO and especially as chairman of the executive board of the organization are not, strictly speaking, researched publications, although I believe they contain interesting ideas on culture, cultural policies and cultural diversity.

I was contemplating publishing them as a contribution to cultural diplomacy education but I doubt if I will find a publisher with an interest in the domain.

He concludes, in the same mail:

‘’if and when I remember or find other potentially useful publications, I’ll forward them to you.

good night

ire o

Ọlabiyi yai’’

The Tree of Knowledge, the River of the Music of Ideas, has gone gently into the night, night to us but illumination to him, taking with him his distillations from his long journey across various continents and thought systems, insights expanded within the nexus of eternity, while those of us left behind in the world of space and time ponder what he has left us as far as we can with our limited faculties honed by effort.

We reflect on his descriptions of the concept of àrè in relation to the ideal of

perpetual dynamism between possibilities, “itinerant individuals,

wanderers, permanent strangers…precisely because he or

she can be permanent nowhere.”

They represent a vision communicated in the expression, “Okosanmijulélo… Oko

san mi ju ilé lo: I am better off on the farm than in the hometown,” in which the "farm

[is] a metaphor for that which is novel,

not ordinary, far from home…contrasted with ilé, ‘home,’ a metaphor for

the daily, the familiar, the given,” in the understanding that “In terms of artistic practice and discourse,

the best way to recognize reality and engage it is to depart from it,” “always [seeking] to depart from current states of affairs[ going about and bifurcating constantly]” as the itinerant of thought,

himself migrating between diverse knowledges, institutions and continents, put

it in “Tradition and the Yorùbá Artist.”

From the ultimate temporal bifurcation into which you have entered, guide us to be mobile and yet stable, dynamic and yet balanced, never at rest in any understanding of existence, probing its depths even as we scan the ever receding horizon for new possibilities.

Guide us to “pìtàn…to "de-riddle" history, to shed light on human existence through time and space [ weaving threads] out of the maze, the riddle of the human historical labyrinth…” in our search for and construction of “ìwà creating beauty by activating and making sensible the noumenal solidarity of the various facets and dimensions of the world, the individual, the society, and the supernatural, which are and must be made to be seen/sensed/heard as tributaries of the same big river” even as we are guided by humility and ambition represented by the expression “Odo laye” “Life is a river,” Who can comprehend a river?, ” your own summations from “In Praise of Metonymy” and your review of Drewal et al’s Yorùbá: Nine Centuries of African Art and Thought, referencing and quoting understandings native to the Yorùbá.

We are not lost to you neither are you lost to us. Free from the limitations of

the flesh you abide in mountains of the mind, radiating vibrations that

penetrate, bringing us nearer to the ultimacy that is “aìkú parí ìwà,” the deathlessness that

consummates existence, as referenced by your

comrade Rowland Abiodun in the unforgettable “The Future of African Art

Studies : An African Perspective,” adapted in

“Ìwà , Ìwà Is What We Are Searching for, Ìwà,” from Yorùbá Art and

Language of which you must have been so proud, a distillation of labors in

which you have been inspirational, as the author states in invoking your name.

“The months and days are the travelers of eternity. The years that come and go are also voyagers. A lifetime adrift in a boat, or in old age leading a tired horse into the years, every day is a journey, and the journey itself is home” states the exponent of an equivalent of your àrè philosophy in a country far from where you discovered this gem.

Like jewels on a necklace you both are, Matsuo Basho and yourself, Japanese thinker, poet and hermit wanderer, you, Yorùbá and Beninoise thinker, prose poet, inter-institutional, interdisciplinary and intercontinental traveller, leading us into where intersect the journey of omoluabi, the Yorùbá ideal of a person, and ideals of the human being generated across ages everywhere.

An Invitation

I invite you to donate to Compcros, from which this essay comes. Part of your donation will be spent on research on the work of Ọlábíyì Babalọla Yáì.

Comments

Post a Comment